Organised recruitment of Irish regiments to the French army dates from 1635 and seven regiments were recruited to fight in France. Harman Murtagh states that the Walls of Coolnamuck, Co. Waterford played a crucial role in this recruitment. While numbers declined in the 1640's, eight regiments fought in French service after the Catholic defeat in Ireland. Wall's own regiment passed to the exiled James Stuart, Duke of York, and disbanded in 1664 (then called the Royal Irlandais).

The most significant military migration to France occurred with the advent of the Williamite wars in the early 1690's, the defeat of James II's army in Ireland, and the Treaty of Limerick (1691). The first mass military migration of troops that would later form the Regiments Irlandais or Irish regiments took place in 1690. In exchange for a contingent of French soldiers sent to Ireland, around 5,000 Irish soldiers sailed from Kinsale to Brest in France under the command of Justin MacCarthy, Viscount Mountcashel. This group formed a foreign brigade within the French army, receiving the higher rate of pay. Soldiers in French military service enlisted for a minimum of six years according to a law of 1682. This term of service was increased to eight years in 1762 but the reality was rather different. Terms of service lasted from a few weeks to decades. The wages of ordinary soldiers were fixed at six sous per day until 1762 when they were raised to eight sous. Foreign troops were paid one sou more per day. Andre Corvisier estimates these wages were equal to that of a tradesman or a peasant, but soldiers had the advantage of receiving pay on Sundays and holidays.

Further migration of Irish troops took place after the defeat of the Jacobite forces, supported by Louis XIV in his European campaign against William of Orange. Under the Treaty of Limerick (1691), the Williamite commander, General Ginkel (1644-1703) allowed for the transport to France of all Irish forces who wished to leave. About 12,000 sailed for France and this group formed a separate army in France under the command of James II and then his son, James III. This army, unlike Mountcashel's brigade, was not part of the French army although the French crown paid the troops.

According to John Cornelius O'Callaghan, the organisation of the Irish regiments in France (in French service and the Stuart army) was along the following lines before the Treaty of Ryswick (1697). The infantry regiments of Clare, Dillon and Lee, with a total strength of over 6,000 troops formed Mountcashel's brigade in French service. The Stuart army in France had ten infantry regiments in seventeen battalions, three independent companies, two troops of Horse Guards and two regiments of Horse, each containing two squadrons, amounting to 12,326 soldiers and horsemen. This gave the Jacobite forces a total strength in France of 18,365.

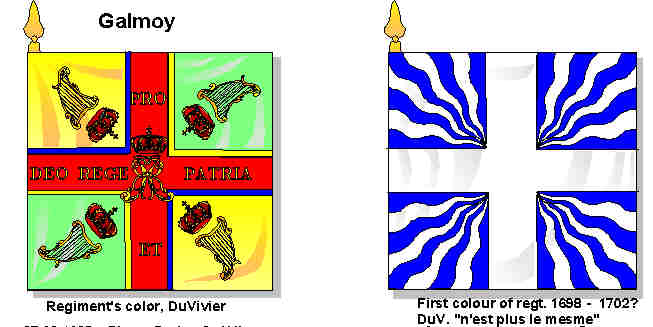

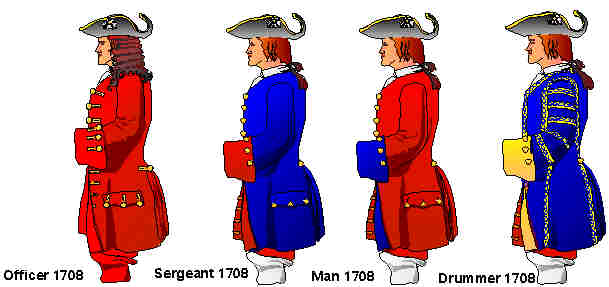

With the return of peace, the French army was reformed in 1698 and the Irish regiments were extensively reduced. Henceforth, the Irish and Jacobite regiments, troops and companies were reorganised into an Irish force in the service of the king of France. As Louis XIV had recognised William of Orange as king of England, he could not openly harbour an army of the deposed king of England and pretender to the throne on his soil. However, this did not change the conviction of the Jacobite forces in his army, as later invasion attempts would prove. As a result of the reform, the infantry was reduced to eight one-battalion regiments of fourteen companies of fifty men, giving a paper strength of 700 men per regiment and a total infantry force of 5,600 men. The regiments were named after the colonel proprietors, Albermarle, Berwick, Burke, Clare, Dillon, Dorrington, Galmoy and Lee. The cavalry were reduced to one regiment of two squadrons, commanded by Dominic Sheldon. Like ordinary French soldiers, the disbanded troops were left to fend for themselves, and many turned to brigandage and begging, reinforcing negative French stereotypes of Irish immigrants.

The War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713) provided employment for all elements of the French army including the Irish regiments. With the end of the conflict, the Irish regiments were again reduced, this time to five regiments. The regiments of Berwick, Clare, Dillon, Dorrington and Lee remained in service, as did Sheldon's cavalry under the new colonel-proprietor Christopher Nugent. Burke's infantry passed into Spanish service, the other regiments were disbanded and the soldiers were incorporated into the surviving regiments. A royal decree of 2 July 1716 introduced a system of troop records to the French army. French regimental commanders were henceforth required to keep precise registers of non-commissioned officers and ordinary soldiers. These records provide the core source for the website of ordinary soldiers in the Irish regiments and can shed new light on the composition of the bulk of the troops in the Irish regiments from 1691 to the French Revolution. In 1791, the foreign regiments were disbanded as a result of French army reforms of the French Revolution. As yet the database is incomplete, including 16000 out of approximately 20,000 soldiers in French service for the period under examination. It is envisaged that the officers and the remaining ordinary soldiers will be included at a later date.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks