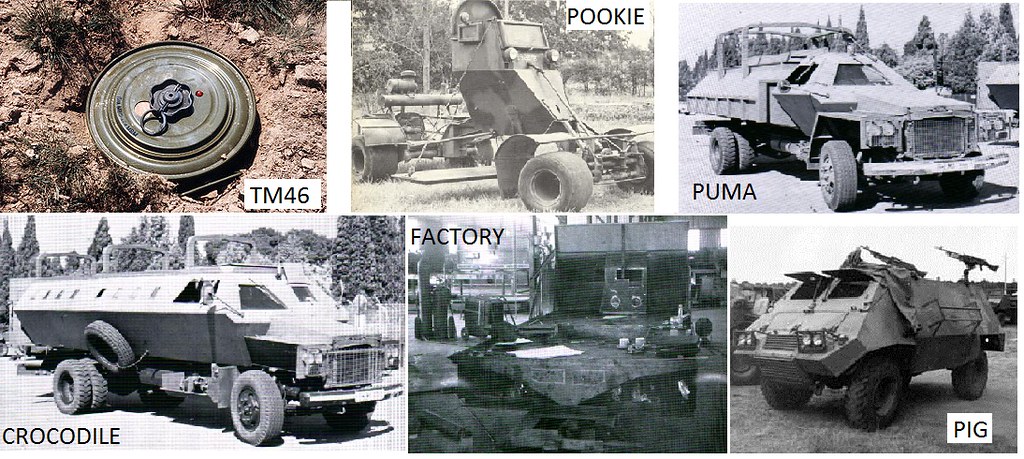

Note: correction to my above post, it was the drive train of the VW Combi that was used for the Pookie. And the tyres for the Pookie were worn out Formula 1 racing tyres sourced from the scrap heap at Kyalami Race Track in Johannesburg, South Africa.

There have been a number of instances where the issue of urgent on the fly modifications or at least bypassing the normal (long and labourious) procurement could have been (or at least should have been) carried out to provide protection for troops traveling on vehicles in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This problem is incapsulated in the 2008 Study: Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) Vehicle Case Study by Franz J Gayl

It chronicles the horror story of a procurement bureaucracy gone mad at an unacceptable cost of life and limb to those fighting the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Worse still it highlights how virtually all serving officers and enlisted men have been numbed into accepting that there is no solution to the problem. See quote below:

My experience here in SWC and reinforced by two recent conversations with long serving US soldiers finds the same. That is that the US soldier has been conditioned to accept that his country will send him into harms way without taking the necessary action to provide them with the necessary (and deserved) protection.It is noteworthy that during the conduct of his 2002-2003 thesis research Maj McGriff continuously encountered push-back from operators at all levels, both enlisted and officer, when presented with the MRAP idea. As if conditioned with a sense of futility, his audiences shared a common first response that 1) the MRAP idea was unrealistic because the Marine Corps would not nor could not afford it and 2) the acquisition system would certainly reject MRAPs because it was something new that differed from/was outside of established Programs of Record (PORs). This same sense of procurement and process futility persisted even while their warfighter audiences agreed that the MRAP made operational common sense.

I sense that the mindset in the US (and probably also the British) military leadership has developed the belief that the best way to protect soldiers is to not expose them to risk in the first place rather than provide them with the best equipment and support available while insisting that closing with and killing the enemy still remains the primary role of the infantry and continues to be their daily operational duty.

The conclusion should be of grave concern:

Anyone freak out over this when it was published? ... or with a shrug was it just treated as a normal day at the office?The MRAP case study has demonstrated that Marine Corps combat development organizations are not optimized to provide responsive, flexible, and relevant solutions to commanders in the field.

The following article remains essential reading in relation to landmine detection systems:

The Pookie - A History of the World's first successful Landmine Detector Carrier by Dr J.R.T. Wood

Bookmarks