Airborne

During 1977, by necessity, the RLI became an airborne commando battalion and parachute training proper was begun. Two troops from 1 Commando had been para-trained toward the close of 1976 in an experiment to get more troops, more rapidly into Fireforce actions. It was a success and para-training rapidly got underway, with two troops from 3 Commando following in January 1977. Support Commando had 24 of its members trained as parachutists by March and thereafter each commando sent troops on a regular rotational basis to New Sarum for training. But facilities at New Sarum were limited and in 1978, the SADF Tempe Base in Bloemfontein, South Africa, stepped into the breach.

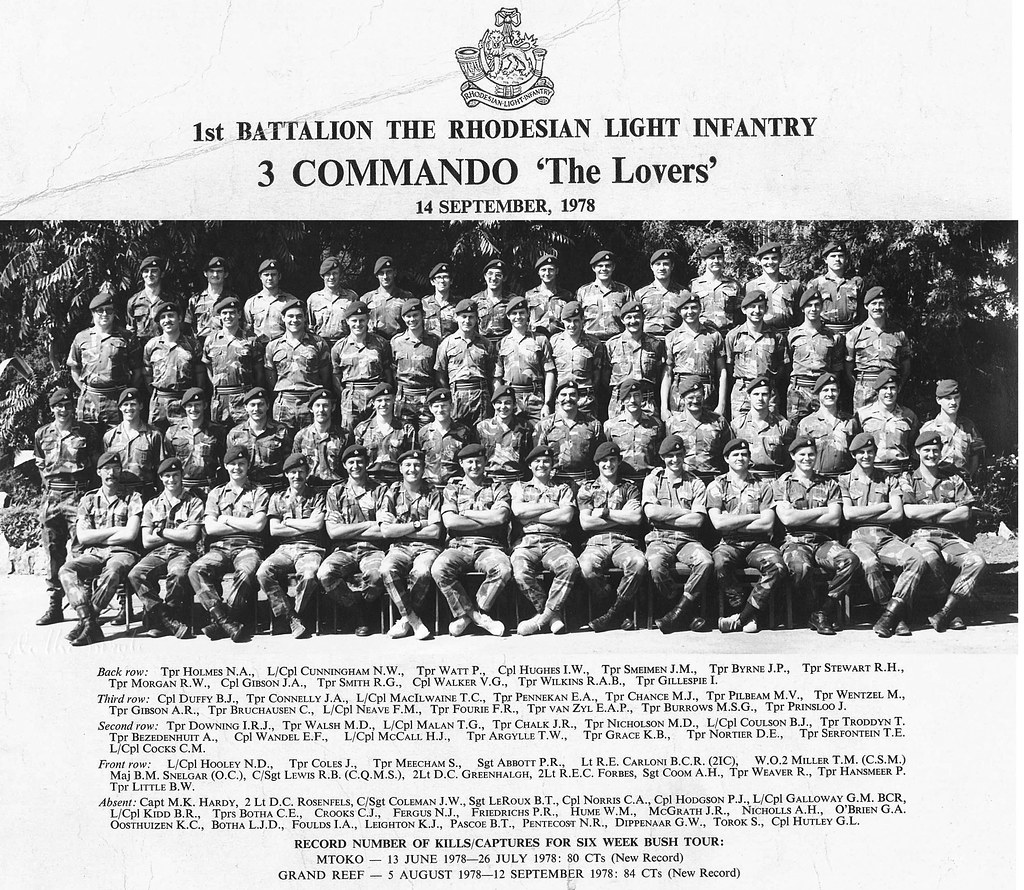

Chris Cocks, a member of 3 Commando, describes the experience: … During the middle of a Mtoko bush trip, we were suddenly told that 11 and 14 Troops were returning to Salisbury for parachute training. At first we didn’t believe it. We knew a troop from 1 Commando had been para-trained in November 1976 but we had thought this was only for experimental purposes. However, with the shortage of helicopters there was only one other way to rapidly deploy troops into a Fireforce action—by parachuting them in. It transpired that the 1 Commando experiment had worked out well. Therefore it had been decided to train the whole battalion. We felt honoured that 3 Commando had been selected to go first, particularly as 11 and 14 Troops were leading the way.

Not everyone was thrilled with the idea, however. Loader was terrified but said he would try. Smit, the MAG gunner, was also terrified and said adamantly, “I’m not going. If God had wanted us to fly he would have given us wings.” Lieutenant Smith tried to reason with him. But Smit stubbornly refused to go and the lieutenant was left with no choice and Smit was posted out of the commando. I was very sad to see him go.

When the day came we found ourselves outside a large hangar at New Sarum Air Base, where the Parachute Training School was housed. The instructors were a happy bunch. There were Rhodesian, British, American and Australian PJIs, and unlike Training Troop, there was no malice in their training methods. Their job was to teach us how to jump … in as short a time as possible. Our training was both extensive and comprehensive. We learned how to land—the mysteries of side-rights, side-lefts, front-rights and back-lefts. They taught us how to exit the Dakota and the drills while still inside the aircraft. We were shown how to guide the lift webs during descent and how to operate the reserve if the main ’chute failed to open … Everybody paid particular attention during that lecture. It was important.

Some of the lads were already para-trained. Furstenberg, for example, had his Special Air Services wings, and Hugh McCall had served in an American Airborne Division. It was old hat to them, naturally, and of course they took every opportunity to tell us so. “Listen sonny,” McCall used to tease, “I was in a T-10 harness before you were in a T-shirt.”

At last came the big day for our first jump. We boarded the Dakota nervously, the packs comfortable but still somewhat alien on our backs, and sat down along the sides. Then the Dakota gathered speed down the runway and took off, and we climbed sedately to a thousand feet. In my stomach a million butterflies felt as if they were moving a lot faster than the plane itself. We were to jump in sticks of two and we waited for the word of command.

Suddenly it came. “STAND UP … HOOK UP … CHECK EQUIPMENT,” bawled the instructor. The roar of the slipstream outside the open exit door almost drowned his words. I rose and hooked the clip to the overhead static-line cable. It was just like the drill … except this time it was for real. I checked my equipment—quick-release box secure and clipped in … reserve secure … lift webs comfortable. The assistant dispatcher came forward and gave us a final check. When he was satisfied he returned to his position at the door.

“ACTION STATIONS,” yelled the instructor. I shuffled forward to the door and put my right hand on the cowling above it to steady myself. My left hand was firmly across the reserve on my chest. Both my hands were sweaty and I realized I was biting my lips. Smit had been right. It was unnatural. I glanced at the instructor. He winked and flashed me a broad grin and I smiled back nervously. Would I remember everything I had been taught? When exiting the aircraft, jump out and not down … look straight ahead … keep your feet together. “STAND IN THE DOOR!” The red light flashed on. Two steps forward … “One two” The slipstream buffeted and distorted my face. Green light on.

“GO!”

‘I leapt out, both arms across my reserve. I was immediately struck by the exhilarating force of the slipstream as it tossed me around like a feather behind the Dakota. Had I done everything I’d been taught to? There was a sharp crack above my head as the parachute opened, and I gazed up with relief at the large expanse of material billowing into a green mushroom above me. So far so good … But everything seemed to be happening too quickly.

Remember the drills! Head tucked in … knees bent … elbows in. The ground rushed up at a frightening speed. Pull down hard on the lift webs and prepare the angle of your body to land with the wind direction. Crunch!

I landed with a hard jolt, but rolled into a side-right in the manner born.

Suddenly I realized that apart from a few bruises I was all right. My first jump was over. A newspaper photographer snapped his camera at me as I gathered in the folds of my parachute, and the next day in The Herald there was a picture of me which I cut out and vainly pinned on my locker back at barracks. Eight jumps, including a night jump, and we were qualified paratroopers. It was one of the proudest moments of my life when I was awarded my wings and on our return to the bush we were regarded with envy by our comrades.

However, jumping operationally, we soon discovered, bore little relationship to the halcyon days of training. The Rhodesians kept paratroopers in the air for as short a time as possible, so as to offer little target opportunity to the enemy on the ground. To achieve this we were supposed to be dropped from a height of five hundred feet. But in reality it was usually lower. On occasions we were inadvertently dropped from altitudes of less than three hundred feet, which gave the parachute barely enough time to open before the ground rushed up to meet you. Rhodesia is rough country so invariably there was a lack of suitable dropping zones in a contact area. This left the pilots with no choice but to drop us into treed areas or onto rocks, and jump casualties were often high … especially when a strong wind was blowing.

Encumbered with bulky webbing and an awkward machine gun strapped to one’s side, could be a frightening experience. Sometimes we jumped with CSPEPs attached to our web straps. CSPEPs are large containers or packs that dangle beneath a paratrooper. They are not only extremely heavy, they also are difficult to jump with as they tend to sway and disrupt the parachute’s course. It is small wonder that RLI paratroopers referred to themselves as ‘meat bombs’.

In very short time, however, the RLI became adept paras. With some aggressive dispatching ‘techniques’ it was not unusual to get a stick of 20 men out the plane in less than 20 seconds. Less than one second per man. The benefit of such a sharp exit was that the troops would land closer together on the ground and be at readiness far sooner to prepare their sweep or advance than if they’d been scattered over a great distance.

It is doubtful whether the Rhodesians’ record of operational jumps will ever be matched. In one year alone, in the late 1970s, over 14,000 operational jumps were recorded. It was not uncommon for RLI troopers to parachute into two contacts a day and on the rare occasion, three. Out of my total 42 jumps, 18 were operational. This was ordinary and there were many paras who exceeded 50 operational jumps. (The record for the most operational jumps in the RLI is held by Des Archer of 1 Commando—a staggering 73 op jumps! Surely a world record in any sense.)

Jumping operationally was not a pleasant experience and I did my damndest to ‘snivel’ and get into the heliborne sticks. I’m sure most RLI paras would agree with me that given a choice between para or heliborne, the vast majority would opt for the latter.

Bookmarks